Final Surge just became one of the first training logs to add the tracking of both running power and running dynamics. We partnered with Stryd to integrate their running with power technology. Also, Garmin just announced they would be adding running power to their suite of devices that already support running dynamics. Therefore, Final Surge will also track Garmin running power and running dynamics. Soon running power is likely to be as integral to running as the bike power meter which has revolutionized cycling training and racing.

Understanding running power begins at the most basic athlete and coach level without the need for equations or physics (if you want all the details, see Coach Jim Vance’s book Run with Power). We remember the skepticism when power meters first came into cycling, so we expect the same for running. For multisport athletes and coaches, the best way to understand running power is to compare it to a bike power meter.

But first we need to ask the most basic question; what’s running power good for? While there are lots of exotic details, astounding science, and cool tech, it boils down to running power is a stable, reliable, reproducible way to measure results from training. There are other measurement methods, such as time/distance/speed and heart rate, each with advantages and disadvantages. Running power simply adds another training measuring method with significant advantages, including providing direct real-time measurements of physiological effort to the athlete without a time lag.

We expect there will be much debate about which one of these is the best measurement method, but we believe the best athletes and coaches will use combinations of these methods to get the most comprehensive and reliable picture of what is, and is not, working in their training.

A bike power meter is at its essence a sensor that measures how much the crank arm (or depending on power meter design, crankshaft, pedal spindle, or hub gear) deflects (or bends) when your leg applies effort to the pedal. That is primarily determined by the riderÍs weight and leg strength, plus the secondary impact of a lot of other variables such as elevation, wind, cadence, temp, etc. If you control for weight (which is why power is often given as a ratio of power to the athleteÍs weight), and for the sake of this discussion on basics ignore the secondary variables, the amount of deflection of the crank arm becomes a valid measure of leg strength.

Since bike mechanics primarily turn crank arm movement into horizontal (i.e., forward) motion, leg strength can be correlated directly to bike performance, resulting in crank arm deflection (power) becoming a reliable measure of performance resulting from training.

The running power meter is surprisingly similar in concept. In running instead of the deflection of the crank arm, they measure the deflection of a base plate under the tread of a force measuring (force-plate) treadmill during foot strike. Just like the crank arm, the amount of force-plate deflection is primarily determined by the runnerÍs weight and leg strength, plus the impact of other secondary variables such as elevation, wind, stride, foot strike, airtime, etc.

Again, if you control for the weight, and for the sake of this discussion on basics, ignore the secondary variables, the amount of deflection of the force-plate becomes a valid measure of leg strength and thereby running performance. If we only ran on treadmills, the running power meter in the form of a force-plate treadmill would have become commonplace long ago.

The breakthrough of Stryd and Garmin is finding other ways to measure the equivalent of treadmill force-plate deflection when running outside without a treadmill. For example, Stryd researchers using 3D motion capture cameras, force-plate treadmills, VO2-Max testing and other sensors, and a whole lot of mathematics to determined that these variables can be precisely correlated with force-plate deflection.

Best of all, these variables could be very accurately measured by a combination of the latest GPS, altimeters, motion sensors, accelerometers, etc. many of which are already available in our training tracking devices. Therefore, when these variables are measured for the runner, it can be accurately deduced how much force-plate deflection, or power, the runner is producing.

Another reason you need additional variables to determine running power is that, unlike the bike which has mechanisms to convert power directly into horizontal motion, a runnerÍs varying form can turn leg strength into horizontal, vertical and side movements. Therefore, the application of power to create performance is more complicated in running than in biking.

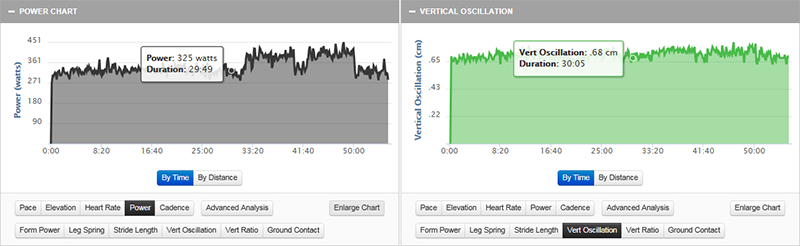

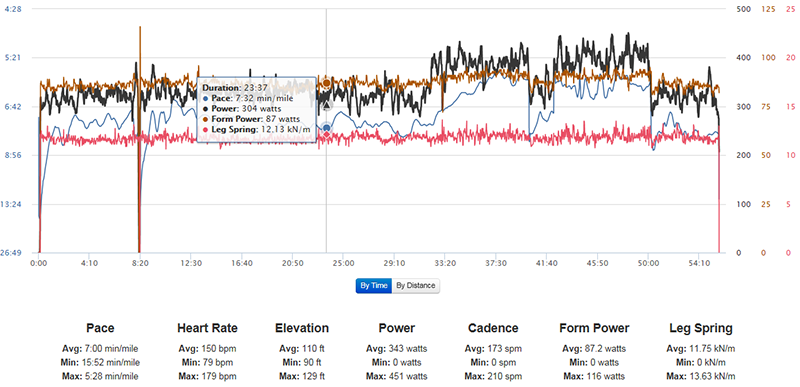

That’s where the Stryd variables and Garmin running dynamics are important beyond predicting power. They can help the athlete and coach fine tune their running gait to make sure most of the power is optimally directed at horizontal movement and performance. This is why Final Surge tracks and reports both running power and running dynamics.

For Stryd, these variables include elevation, cadence, ground contact time, vertical oscillation, and leg spring stiffness (LSS). For Garmin, the variables are running cadence, vertical oscillation, vertical ratio, ground contact time, and ground contact time balance.

Garmin running dynamics, which has been around for a while for running gait improvement, can now also be used with new software and the barometric altimeters in certain Garmin watches, such as Vivoactive HR, Forerunner 735XT, Forerunner 935, Fenix 5, 5S, and 5X, to determine running power.

Garmin has the running dynamics in their separate RD Pod (which you clip to your waistband in back) or in their HRM-TRI/HRM-RUN chest straps. Interestingly, if you already have the Garmin RD Pod or HRM-TRI/HRM-RUN chest straps, you will just have to install a Garmin IQ App to get running power. The newest Stryd device contains everything in their foot pod, which is particularly nice if you have the HRM on your watch, or a standard HRM chest strap with a less pricey sports watch.

On the bike, the power meter can confirm for the athlete and the coach that a particular bike training effort either improved power or did not. If it did improve power, that training effort could be emphasized. It works the same way on the run. If a particular running training effort improved power, that training effort could be emphasized.

Check out the recent DC Rainmaker review of Garmin Running Power (which also discusses the Stryd Running Power).

At Final Surge, we support both Stryd and Garmin running power and running dynamics as part of our full suite of training metrics we track. We believe running power will soon become as standard as the time/distance/speed and heart rate methods to even more reliably measure training progress.

Team Final Surge